One of my more persistent pandemic-era hobbies has been developing, designing, and illustrating fictional characters for multiple ongoing Dungeons & Dragons campaigns with friends. It’s a case of “projects beget projects” meeting “the right tool for the job,” growing awkwardly out of my found-texture fantasy map project, and not completely realized until I began using HeroForge, one of many custom character design engines out there.

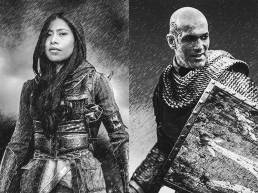

It was much rougher going than my map work, even though both came from the same impulse: reviving a teenage creative hobby to refine and realize it with a middle-aged brain and professional design skills. Unlike the maps, though, I didn’t have much to start with—all my childhood character portraits have long since been lost—so visualizing my new bards, rogues, and rangers had to start from scratch. For better and worse, that meant mashing together internet-sourced imagery of people and gear into composite montages that would probably horrify actual life-drawing artists, but which were better than nothing.

However they didn’t feel “original” enough, despite being relatively creative jalopies fed through umpteen filters, so when I found some fun free AI colorizers (the kind that clumsily impose color on old photos), I tried those out too. The results were interesting—a bit like turning my characters into Turner Classics movie stars—and got more so when I superimposed them on more internet-sourced imagery for backgrounds. All of that went through more PS Express filters on my phone for the sake of “originality,” but something still didn’t feel right.

When I tried creating illustrations for my friends’ characters, it became even more glaringly obvious that these composite images were just that. These characters still didn’t seem like real people, which for us was the attracting aspect of D&D 5e’s story-based role-playing, so I let them go for a little while to focus on yet another D&D-related side project: a sourcebook-style compilation of everything I’d developed to date for my homebrew campaign (maps, histories, etc.). That featured a few of the montages, but ultimately proved to be a momentary dead end, so maybe I’ll revive it sometime in the future.

Two things got me inspired and back on track designing characters: an umpteenth bingeing of old Star Wars cartoons (“Rebels” and latter-day “Clone Wars”) which effortlessly breathed life and emotion into computer-generated characters, and a recommendation from one of my fellow D&D player-gamemasters to check out online map generators like Inkarnate (which I didn’t need) and character renderers like HeroForge (which I absolutely did need). After about an hour playing with HeroForge, I was off to the races.

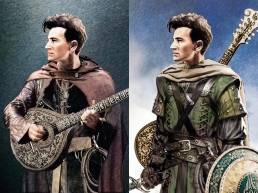

Other people have written insightful Heroforge reviews, so I’ll simply add that once I got over the shallow idea of characters not “looking real,” the Heroforge rendering engine became as versatile and useful a tool as when I first worked with Photoshop 2.0 over two decades ago. I didn’t need to create actual human-looking people—I’m not out to make deepfakes or Westworld hosts—I just needed to visually represent these characters in a relatively unique way, to help me better role-play them for two hours a week. Ironically, a template-based rendering engine (albeit one that’s constantly adding new features) has been the perfect way to do that.

I stopped creating montages immediately—they were laborious and clunky in Photoshop—and got inspired by the myriad Heroforge options so much that it became one way to jumpstart character development. I often had the image before the backstory or anything else, which was great story fuel: “Who is this person and why do they appear this way? Why do they have that gear? Where would they be from on the map?” From there it was a quick (and kinda expensive) jump to printing out my favorites as mini-figures.

After a test-run of one STL file on my stepfather’s 3D printer (which he got to augment his model railroad hobby), I decided that the costlier (but meticulously detailed) pro prints would work better. My “Dirty Dozen” collection was complete about the same time as my old phone died, so a new device with a better camera was the only excuse I needed to stage snapshots with dice and superimpose the digital models with Photoshop. It does feel a bit like I’ve reached my “old man painting miniatures” phase, but as a kid I always wanted to make my own action figures. Maybe that’s why I’m doing this.

After living with these people in my head for 18 months, they’ve become as real to me as characters from any favorite story, film, show, or book (even my own). That combined with Heroforge’s ever-more-detailed updates and adjustments inspired me to go all-in with portraits of each. It was still an awkward process—zooming in using my phone because the laptop can’t, then editing in PS Express before fine-tuning in full-blown Photoshop—but the results work well, or at least well enough before the tool gets updated and I go back and re-edit them all over again.

On one level this project feels super-frivolous and self-indulgent, especially when I’m only pulling in a few freelance design projects here and there. But when I was last underemployed, circa 2003, I dove into dozens of little pseudo-hobbies, and one of them (graphic design) ended up being my “career” for the next 17 years. “Tinkering with character design using a tool someone else created” is the same as tinkering with any idea using free (or eventually prohibitively expensive) software.

The key is to keep creating at a low hum, figure out what makes it interesting, and a hobby might snowball into a “career.” Or not! This is also just fun to do! Creating a map of a made-up place was only step one (and probably done out of order). Maps are more compelling if they’re populated with interesting inhabitants, right? Though yes, it would be nice to have a finished map poster to stare at while I do this other stuff. Maybe that’s next.